An alternative to the standard fixed-rate mortgage is an adjustable-rate mortgage, also known as a variable-rate mortgage. With the standard fixed-rate mortgage, once you sign the mortgage agreement, your monthly payment is fixed for the life of the loan or until you sell the house or refinance it. An adjustable-rate mortgage is one in which your monthly payment can change over time.

Why would anyone ever want an adjustable-rate mortgage instead of a fixed-rate mortgage? There are two main reasons: (1) the mortgage interest rate might be high and you expect it to decline; and (2) on average, adjustable-rate mortgage interest rates are lower than fixed-rate mortgage interest rates. Since the early 1980s, the interest rate on fixed-rate mortgages has declined fairly steadily. As we will see, if you had bought a house in the early 1980s, you could have definitely profited by getting an adjustable-rate mortgage, which would have almost continuously adjusted downward. Generally, when the interest rate on fixed-rate mortgages is temporarily high, you may be better off with an adjustable-rate mortgage.

The way that adjustable-rate mortgages work is that they adjust your monthly payment every year (or sometimes every three years) depending on the movement of market interest rates. Many people don’t like that feature of adjustable-rate mortgages because they dislike the risk involved in not knowing what their mortgage payment will be. But if you can stand the risk, it can save you money. What you need to figure out is whether you can handle your monthly payment if interest rates go up and you have to pay more.

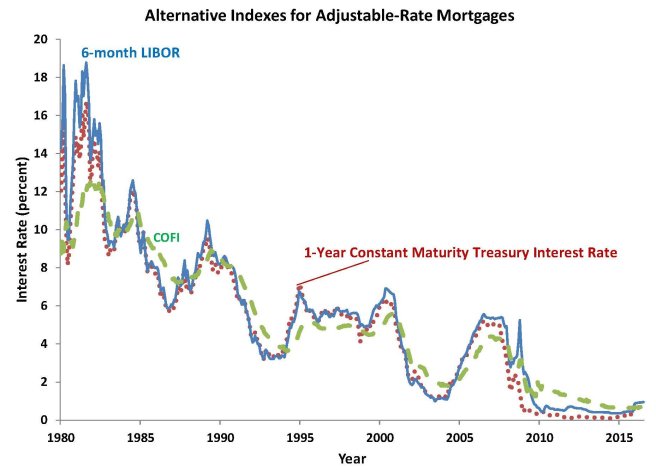

The interest rate on an adjustable-rate mortgage loan has two pieces: an index rate and a margin. Add the two and that is your interest rate. The index rate is an interest rate that moves with interest rates in the overall market. Examples include the one-year constant maturity Treasury index, the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), and the cost-of-funds index. Each represents a typical market interest rate. The one-year constant maturity Treasury index is a rate calculated by the Federal Reserve Board as the average interest rate on a Treasury bond with one year until it matures and the bond is paid off. LIBOR is the interest rate that banks in London pay each other for short-term loans in dollars; it is relevant for U.S. loans because there is a close tie between banks in the United States and in London, as they often enter into “swap” agreements to reduce their risk. A common index used for adjustable-rate mortgages is the 6-month LIBOR. The cost-of-funds index is the monthly weighted average cost of funds for savings institutions in the 11th district of the Federal Home Loan Bank.

The chart shows the movements of these rates over time. You can see that they all move fairly closely together, but there are some differences between them at various times. When interest rates in the overall market are declining, the cost-of-funds index is generally slower to decline than the other measures, as you can see in the mid-1980s, early 1990s, early 2000s, and from 2010 to 2013. When interest rates rise, the cost-of-funds index is usually slower to rise than the other indexes, as you can see in the early 1980s, 1994 to 1995, 1999 to 2000, and 2004 to 2006. The fact that the cost-of-funds index is slow to rise when other rates rise is good for borrowers in those times, but the fact that it is slow to fall when other rates fall is bad for borrowers in those times. On average, all the rates move together, so one particular rate is not better than the others. The one-year constant maturity Treasury rate and the 6-month LIBOR rate generally move closely together. A larger-than-normal discrepancy between them occurred in the financial crisis when LIBOR was set in an odd manner, which suggests that you might prefer to have the one-year constant maturity Treasury index or the cost-of-funds index for your adjustable-rate mortgage.

Chart: Alternative Indexes for Adjustable-Rate Mortgages

Source: Federal Reserve Board data on 1-year constant maturity Treasury interest rate and LIBOR rate, Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco for COFI index