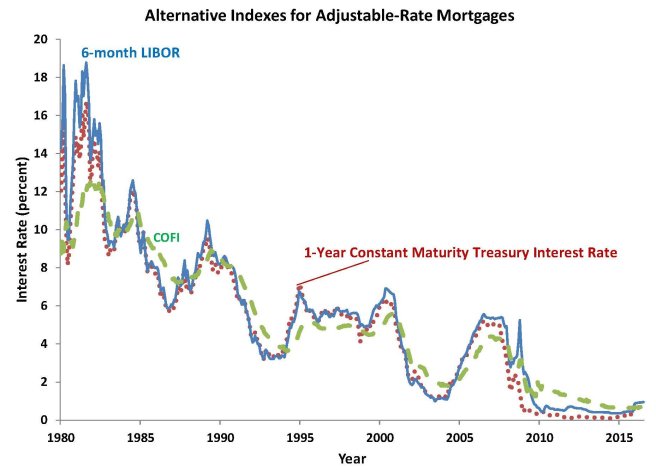

In the two previous blogs on adjustable-rate mortgages, we discussed various indexes that are used to determine the interest rate on an adjustable-rate mortgage and we compared the interest rates on adjustable-rate mortgages to those on fixed-rate mortgages. In the last blog, we showed a chart that gave you an idea about how to compare the interest rates on the two types of mortgages over time. But it isn’t a very good chart to answer a key question: at any date, would I have been better off with a fixed-rate mortgage or a variable-rate mortgage? That is a more complicated question because it depends, in large part, on how long you plan to keep your house and how expensive it is to refinance your mortgage. Let’s think about two different scenarios and show you when you would have been better off with a fixed-rate mortgage versus a variable-rate mortgage. We’ll compare a fixed-rate mortgage of $100,000 at each date to a variable-rate mortgage in which your index is the one-year constant-maturity Treasury rate with a margin of 2.5 percentage points, with a 2 percentage point annual cap and a 5 percentage point lifetime cap, with a fixed initial teaser rate for 3 years that gives you a 1 percentage point lower initial rate. In scenario A, we’ll assume you keep your home for 10 years; whereas in scenario B, we’ll assume you keep your home for 20 years. If you save money on one mortgage versus the other, we assume that you will invest it in a one-year Treasury security, which has a similar yield to many other safe investment opportunities.

The results, shown in this new chart, are a bit of a surprise because they show that homeowners would have been better off with adjustable-rate mortgages rather than fixed-rate mortgages, if they had bought their houses any time after 1980.

Chart: Net Profit from Adjustable-Rate Mortgage Over Fixed-Rate Mortgage

Source: Author’s calculations, based on Federal Reserve Board data on 1-year constant maturity Treasury interest rate; Federal Reserve Board data on fixed-rate mortgage rate

Here’s how to read the graph. The origination date (when the house was purchased) is shown on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows the net profit from having an adjustable-rate mortgage rather than a fixed-rate mortgage, adjusted for inflation, in thousands of dollars. We consider a family keeping a house for 10 years or 20 years. A positive net profit for a line on the graph shows that someone getting a mortgage at the date on the horizontal axis would have been better off with an adjustable-rate mortgage; a negative net profit means the person would have been better off with a fixed-rate mortgage.

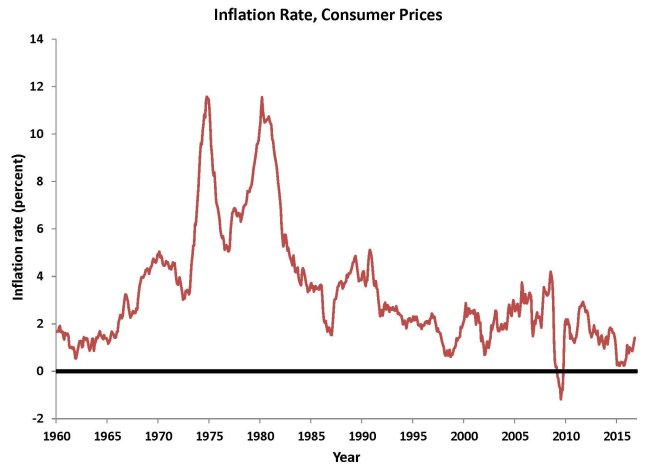

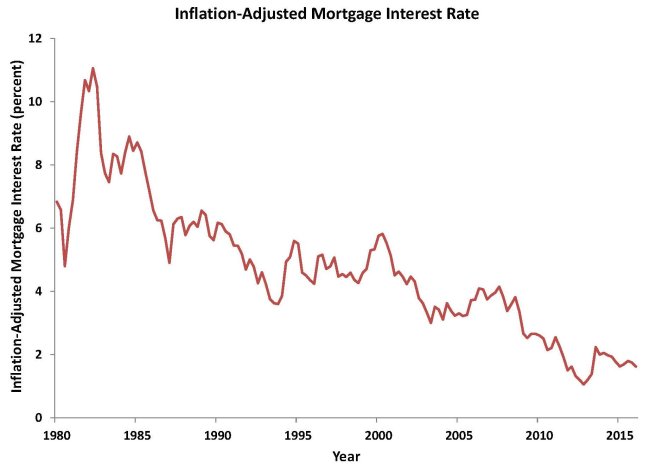

You can see that the turning point is the period when inflation was at its highest, in about 1980. Anyone who got a mortgage before that date would have been better off with a fixed-rate mortgage. For example, a family that took out a mortgage loan in 1973, stayed in its house for 20 years, and had a fixed-rate mortgage, would have been $200,000 better off in 1993 than a similar family that had an adjustable-rate mortgage. But starting in 1980, which is the period in which the inflation rate peaks and then begins to decline, an adjustable-rate mortgage gives a net profit over a fixed-rate mortgage. For example, a family that took out a $100,000 mortgage in 1981, stayed in its house for 20 years, and had an adjustable-rate mortgage, would have been $280,000 better off in 2001 than a family that had a fixed-rate mortgage.

However, once we get into more recent periods, we see a pattern that is not surprising: adjustable-rate mortgages provide a small net profit over fixed-rate mortgages. This is not surprising because an adjustable-rate mortgage is riskier than a fixed-rate mortgage to the homeowner. The compensation for taking such a risk is the net profit. So, here is the bottom line: you can save money, on average, by getting an adjustable-rate mortgage, but it is riskier than having a fixed-rate mortgage. If the inflation rate increases after you get your mortgage, which is the main factor raising mortgage interest rates, then you will be better off with a fixed-rate mortgage. That’s the result we see in the chart for mortgages that were originated in the 1970s. But, if the inflation rate stays the same or decreases after you get your mortgage, then you will be better off with an adjustable-rate mortgage.

In recent years, the Federal Reserve has committed to keeping the inflation rate low and stable, as we will discuss in a later blog. If you believe that their commitment is credible, then you may want to get an adjustable-rate mortgage. But you must be aware of the risk that your monthly payment could rise. If your budget is tight, you will probably be better off with a fixed-rate mortgage to avoid that risk. And the net profit from having an adjustable-rate mortgage stayed pretty low for mortgages originated in the 1990s and early 2000s, so the cost of having a fixed-rate mortgage instead of an adjustable-rate mortgage is not great.

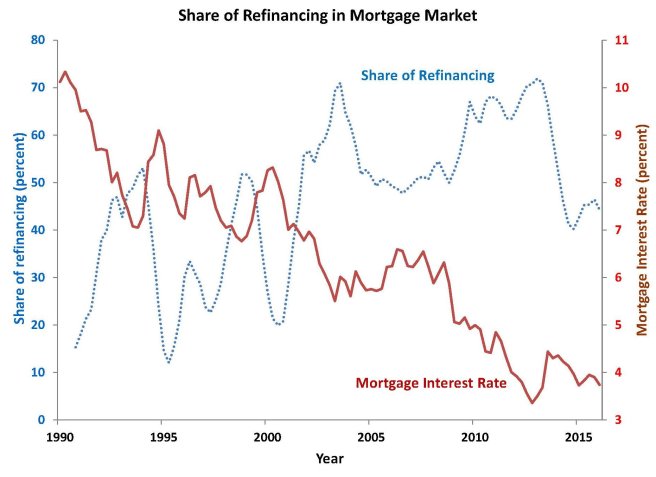

Refinancing

The analysis that we discussed above is not entirely foolproof because it did not consider the possibility of refinancing a mortgage. Had you taken out a fixed-rate mortgage in 1981, for example, you most likely would have refinanced it a few years later when interest rates declined. So, one additional consideration that we did not account for in the chart was the likelihood that someone would refinance. Thus, the net profits plotted in the chart are higher than would actually be the case. Still, the chart shows you the net profit if you never refinanced your mortgage. Of course, refinancing can be expensive, but should certainly be done if you have a fixed-rate mortgage at a high rate and you can lower your rate and your monthly payment.

Predicting Interest Rates

You might think that one way to choose between getting an adjustable-rate mortgage or a fixed-rate mortgage is just a matter of forecasting interest rates. In fact, if you could forecast interest rates better than other people, you could make a good choice. But remember that lenders are also forecasting interest rates. Unfortunately for both lenders and borrowers, interest rates are extremely difficult to forecast more than a year or two ahead, which is much too short a time to be of value in choosing a 30-year mortgage.